The U.S. Supreme Court has slapped down a California state appellate court, as a unanimous high court ruled the state court wrongly decided to block an El Dorado County man from suing the county for allegedly forcing him to pay a $23,000 traffic impact fee as a condition of obtaining a building permit to build one house, an act the man said amounts to an unconstitutional taking of property, if not "extortion."

“Holding building permits hostage in exchange for excessive development fees is obviously extortion,” said Paul Beard, partner at Pierson Ferdinand, one of the attorneys who represented plaintiff George Sheetz in the case.

“We are thrilled that the Court agreed and put a stop to a blatant attempt to skirt the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition against taking private property without just compensation.”

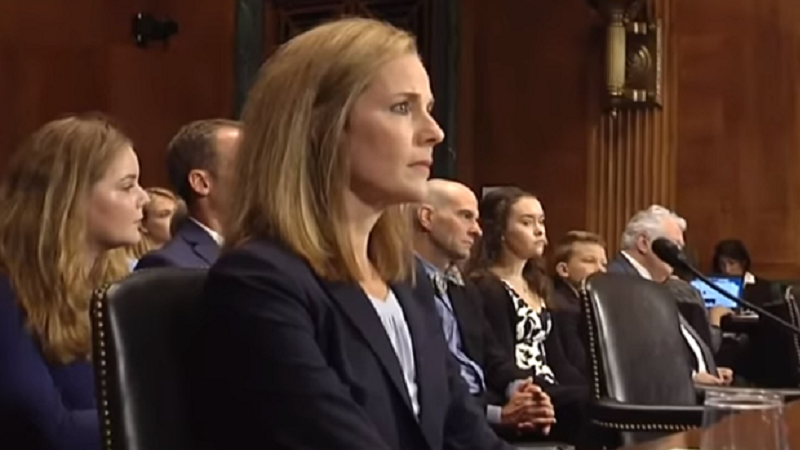

California Third District Appellate Court Justice Elena Duarte

| https://www.courts.ca.gov/

Sheetz had sued El Dorado County after the county forced him to pay more than $23,000 to obtain the permit needed to legally build a small home in unincorporated El Dorado County for him, his wife and their grandson.

According to court documents, the county demanded the money as a so-called traffic impact fee.

The fee was established under county ordinance, with the county arguing the fee was needed to address road expenses the county must pay as it continues to add population, essentially shifting the costs to address future road repairs and construction to new residents or those building new homes and businesses.

Sheetz and his lawyers, including those from the Pacific Legal Foundation, argued the fees are actually unconstitutional, as they bear no real connection to the purpose the county claims.

Sheetz, however, lost in state court. In the most recent state court decision, the California Third District Appellate Court in Sacramento ruled the ordinance passes constitutional muster because the constitutional prohibition on taking property under the Fifth Amendment doesn't apply to ordinances or laws enacted by legislative bodies, like the El Dorado County Board.

That decision was authored by Third District Justice Elena J. Duarte. Justices Andrea Lynn Hoch and Laurie M. Earl concurred in the ruling.

Sheetz appealed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the court ruled 9-0 that the Third District Court's constitutional reasoning in this matter was nonsense.

The Supreme Court's opinion was authored by Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

In the decision, Barrett stressed that the Fifth Amendment applied equally takings that may be carried out by any law, ordinance or rule, by any branch of government, in every state in the Union.

"... There is 'no textual justification for saying that the existence or the scope of a State’s power to expropriate private property without just compensation varies according to the branch of government effecting the expropriation,'" Barrett wrote.

"Just as the Takings Clause 'protects ‘private property’ without any distinction between different types,' it constrains the government without any distinction between legislation and other official acts.

"So far as the Constitution’s text is concerned, permit conditions imposed by the legislature and other branches stand on equal footing."

Further, Barrett said the decision does not address legitimate land use regulation by local governments. She specifically cited the example of a county or city requiring developers to hand over land to accommodate the widening of roads to address increased traffic concerns.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, with justices Elena Kagan and Jackson, added a special concurring opinion that the decision does not "address or prohibit the common government practice of imposing permit conditions, such as impact fees, on new developments through reasonable formulas or schedules that assess the impact of classes of development rather than the impact of specific parcels of property."

But Barrett and the court stressed that any governmental permit fee demands must carry a "sufficient connection to a legitimate land-use interest."

If they do not, Barrett said, "they amount to 'an out-and-out plan of extortion."

As an example, Barrett raised the extreme hypothetical scenario of a local planning commission conditioning the issuance of a permit on the applicant's willingness to host the commission's "annual holiday party in her backyard."

"The landowner is likely to accede to the government's demand, no matter how unreasonable, so long as she values the building permit more," Barrett wrote. "So too if the commission gives the landowner the option of bankrolling the party at a local pub instead of hosting it on her land."

"... A permit condition that requires a landowner to give up more than is necessary to mitigate harms resulting from new development has the same potential for abuse as a condition that is unrelated to that purpose."

Barrett and the court further declared that government's are no less bound by the Fifth Amendment's takings clause when assessing fees against "a large class of properties or a single tract or something in between."

"The Takings Clause, the Court stresses, is no 'poor relation' to other constitutional rights," Barrett wrote. "And the government rarely mitigates a constitutional problem by multiplying it.

"A governmentally imposed condition on the freedom of speech, the right to assemble, or the right to confront one's accuser, for example, is no more permissible when enforced against a large 'class' of persons than it is when enforced against a 'particular' group. If takings claims must receive 'like treatment,' whether the government owes just compensation for taking your property cannot depend on whether it has taken your neighbors' property too."

The Pacific Legal Foundation lauded the decision as an important victory for property rights, noting the Supreme Court has definitively ruled that governments cannot use the building and development permitting process to "coerce owners into paying exorbitant development fees."

Further, the PLF said it believed the ruling will help California and other states address housing shortages, by removing "costly barriers to development."

The case will return to California state court to determine if the fees imposed on Sheetz are proportional to the amount of traffic his small manufactured home will impose on roads in a rural section of El Dorado County and can pass constitutional muster under the test now put in place in the new Supreme Court ruling.